Taq-e Bostan, a Must-see on Traveling to Iran

The historical architecture of every nation is the mirror of its history, art, and culture. The Sassanid inscriptions in different places of Iran manifest the glory and grandeur of Sassanid dynasty. They tried to flaunt their power and splendor by inscriptions and relics on the mountains located on main ways such as Silk Road where could attract all passersby’s attention. Taq-e Bostan in Kermanshah province is one of the most magnificent Sassanid rock reliefs displaying the power of Sassanid kings to the posterity. It is a must-see on Traveling to Iran narrating one of the most sublime parts of the history of Iran carved on the stone.

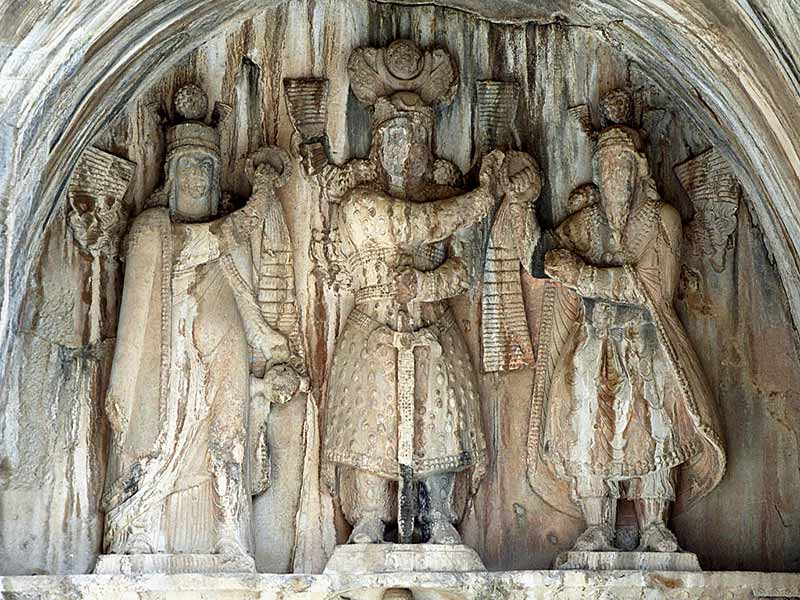

Taq-e Bostan- a site with a series of rock reliefs carved on a mountain near a spring streaming into a pool at the base of the mountain in Kermanshah– consists of a rock relief and the two rock-cut arches one of them larger than the other. The larger arch is 9 m high. According to most Iranologists, it dates back to Khosrow II (around 4th century AD). This relic gives a lot about the beliefs, religious tendencies, clothes, and jewels of Sassanid era. It shows the coronation of the Sassanid king. The king is standing on a platform, his left hand on his sword and his right hand is stretching toward Ahura Mazda on his right hand side. Ahura Mazda is giving a beribboned ring to the king. On his left hand side, Anahita is standing while keeping the jar of water in her left hand and another beribboned ring in her right hand.

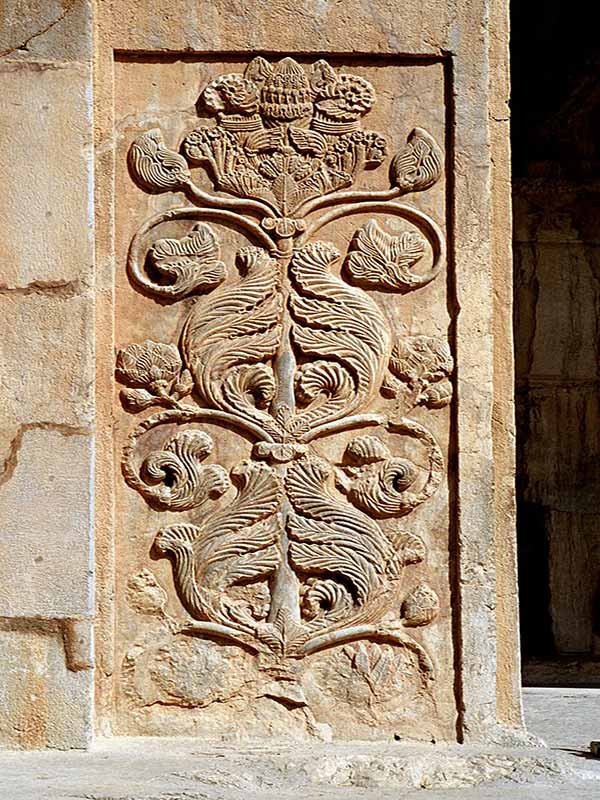

There are two winged female angels on both opposite sides of the arch each has a ring in one hand and a bowl in the other. At the front of the arch, the sacred tree or the tree of life is finely carved.

At the bottom, there is a figure of a man riding on a strong horse. Some Islamic historians believe that the figure is showing Khosrow Parviz over his horse named Shabdiz. The relief is about 4 m high.

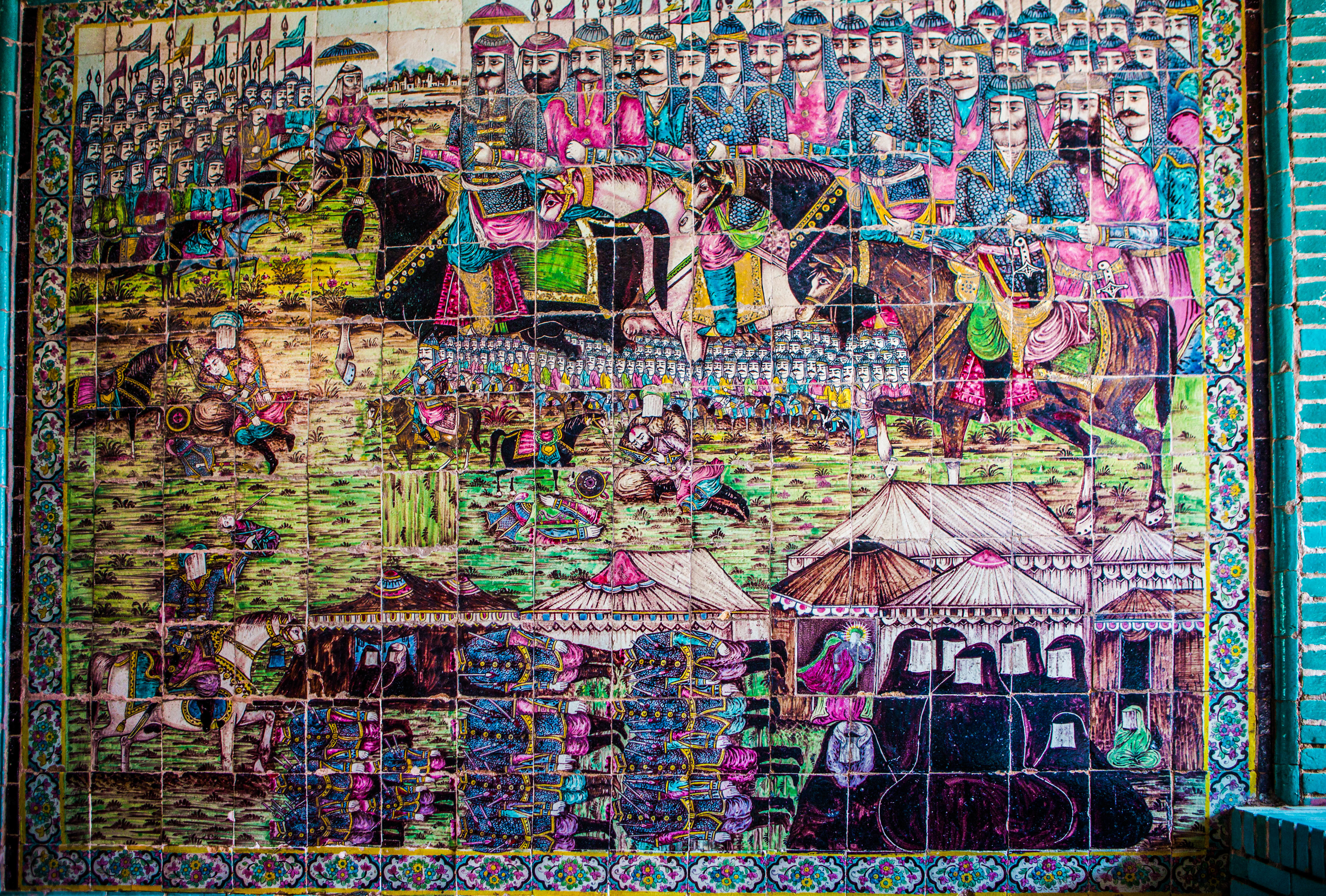

On the sidewall, the royal hunting scenes have been inscribed. The king is hunting the deer while three lines of women are standing politely behind him. The last line is showing the female musicians. The mahouts are trying to direct a herd of deer to the hunting ground and some cameleers are carrying the prey over camels. The relic presents the process of hunting in three episodes: preparation for hunting, hunting, and the end of hunting. On the left wall, the king is chasing the boar.

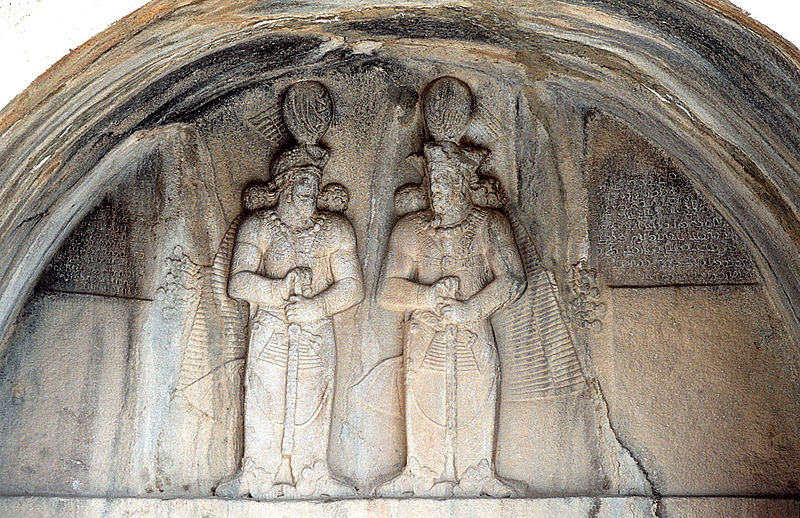

The smaller arch, with 5 m high, is showing the figures of Shapur II and his son, Shapur III. They are standing while facing each other and their hands are on their swords. There are also two inscriptions in Pahlavi and Middle Persian languages on the upper part of the back wall identifying both kings.

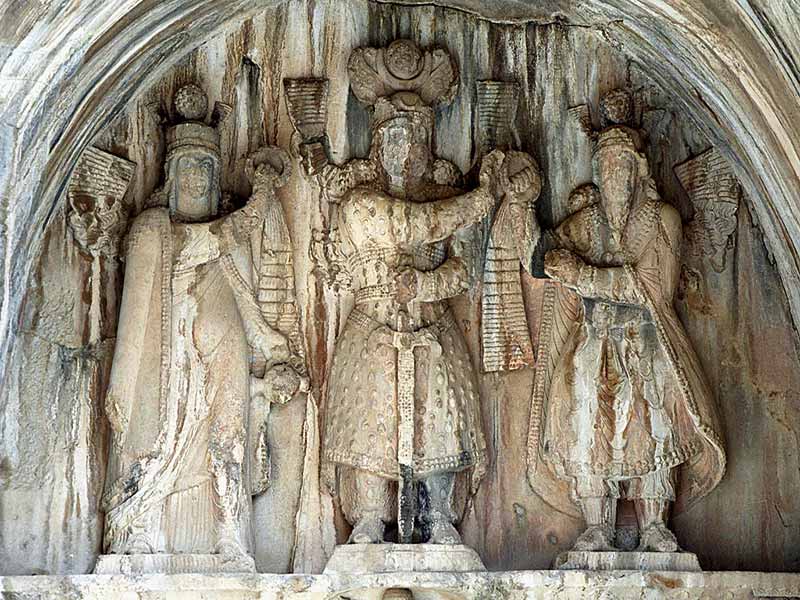

On the right side of the small arch, there is another relic (the oldest in Taq-e Bostan approximately 4 m high) depicting the coronation of Ardashir II (379-383 AD). He is taking a beribboned ring from his predecessor Shapur II or Ahura Mazda on his right. On his left, the god Mithra is standing on a lotus flower keeping Barsam (a plant used in religious rituals) in his hand. A defeated enemy, who is believed by most experts as the Roman king named Julianus Apostata- killed by Ardeshir II in 362 AD. – is laid under the feet of Ahura Mazda and the king. Some experts also say he may be Artabanus IV, the last Parthian king.

As it was mentioned before, all these relics can show great details about the clothes and jewels used by the kings and people in Sassanid era. As an example, the king riding over the horse is wearing colorful clothes decorated with woven golden threads and geometrical shapes. At the scene of boar hunting, the king’s clothes are ornamented with the figure of the Simurgh. All the kings depicted on the reliefs are wearing the necklace and earrings. Their clothes consist of a knee-length coat, long loose folded pants, and a belt around their waists. They have bushy hair, eyebrows, and beard. There are many details carved on their thrones too. The clothes of the entourage are decorated with the figures of plants and birds.

Traveling to Kermanshah, you can kill two birds with one stone! Not only can you visit Taq-e Bostan, a must-see that no one should miss on his or her travel to Iran, but also you can visit Bisotun, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Moreover, do not forget about going to the traditional restaurants to try Dandeh-kebab!