The history and design of Niavaran Palace

Culture tour to Iran includes visits to graceful attractions dating back to different period of Iran’s history. This article introduces one of the most splendid attractions in Tehran that should not be missed in your travel to Iran. There is a historical construction in the middle of an elegant garden in the northern part of Tehran called Niavaran Palace. Covering an area of 9000 square meters, it comprises five buildings. Niavaran Palace was in fact the famous Qajar king’s, Naser al-Din Shah, summer resort which was later expanded by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The main Niavaran Palace was completed in 1968, which was supposed to be a reception hall for royal guests, but changed into the royal residence later. The king and his royal family lived here until the Islamic revolution in 1979.

After the revolution, the palace was conquered by revolutionary forces, however, three years later it was transferred to Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. The complex was open to public in 1986 for the first time.

Its interior design is inspired by Iranian architecture and a touch of modern technology. Although the interior decoration and furniture has been designed and implemented by a French group, a stunning combination of Iranian pre and post-Islamic art is evident in it. There are some precious paintings by Iranian and foreign artists, valuable French and German dishes and treasured Iranian carpets all over the place. The harmony of carpets and curtains is quite eye-catching.

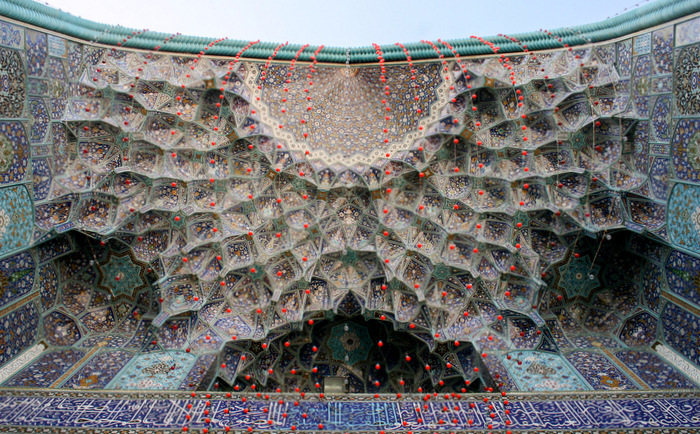

The palace is constructed in two floors and a half; the first floor enjoys a great hall for VIP guests and several rooms including a dining room, waiting room halls and a private cinema. The bedrooms of all family members are situated in the second floor, the half floor was also allocated to Leila, the youngest family member. Its architectural design is by Mohsen Foroughi, plaster work has been carried out by Master Abdollahi, mirror work by Master Ali Asghar and tile works by Master Kazempour and Ilia.

Sahebqaraniyeh Palace

Sahebgharaniyeh is the oldest building of Niavaran palace which was constructed as a summer resort for Naser al-Din Shah, it became his favorite resort later; although, however, he never chose to live there permanently. His son Mozafar al-Din Shah made slight changes to the building later. And, the building underwent greater changes during Mohammad Reza Pahlavi reign.

Sahebgharaniyeh is a white building with green gable roof. Graceful Persian architectural elements such as mirror work, colorful glasses and delicate gypsum are noticeable in this construction. There are magnificent paintings everywhere in this palace, most of them portraying Qajar kings and landscapes in Iran.

One of the most magnificent parts of this building is the mirror hall, which is also known as “Jahan Nama” hall. The mirror works in this huge hall is extraordinary. The northern and southern windows of the palace overlook a view of Shemiran mountains in Tehran. Mirror hall was mainly used for formal parties a meeting and its reputation is primarily due to the

“Persia Constitution of 1906” signed by Mozafar al-Din Shah in this palace.

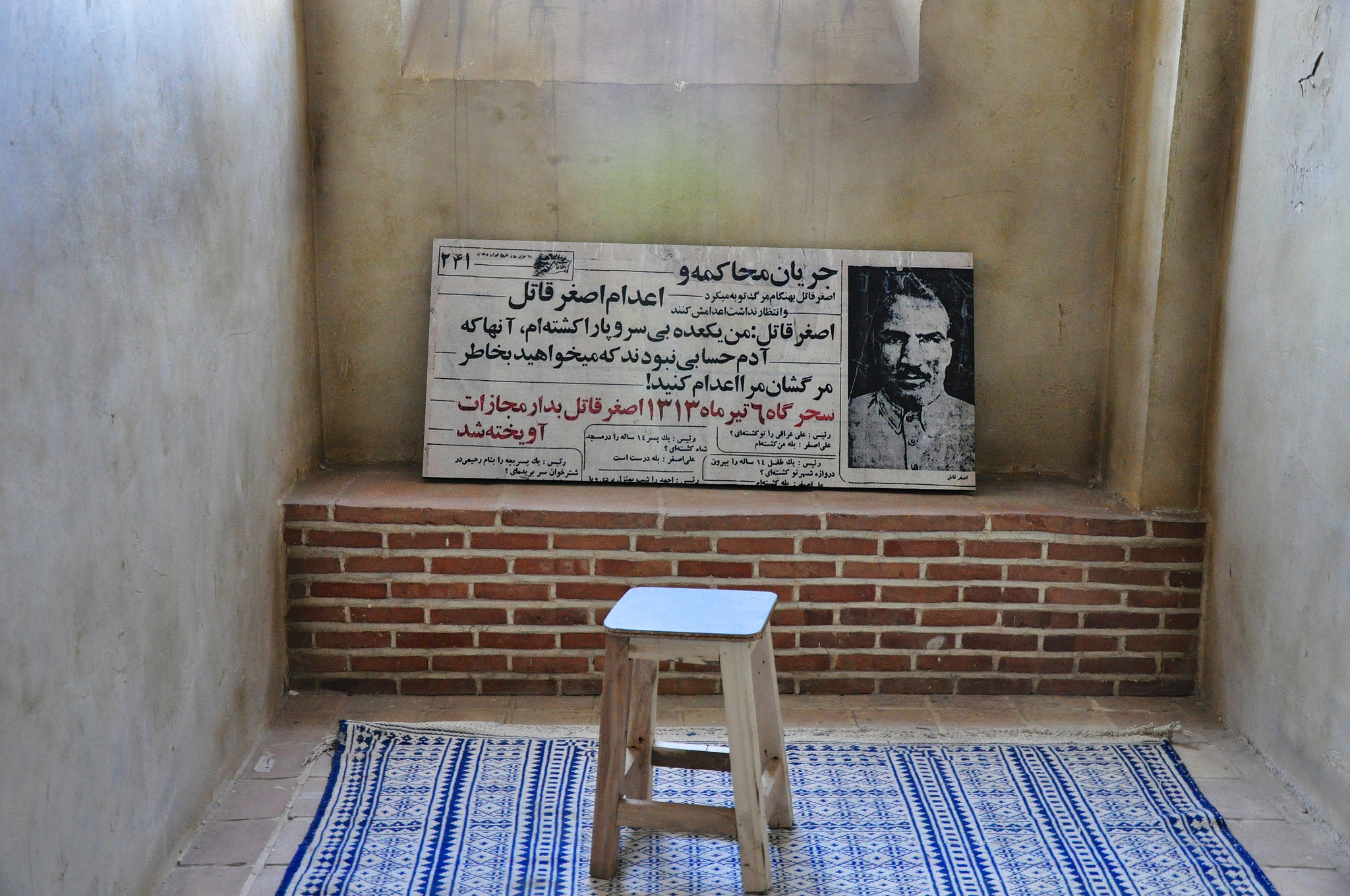

Ahmad shahi Pavilion

Ahmad Shahi pavilion is a two-story building with an area of approximately 800 square meters. The architectural design is especially unique and graceful compared to the other buildings in this complex. There is no concrete evidence of its construction date, some attribute it to Ahmad Shah’s summer resort, the last Qajar king who ruled for a short time. Therefore, it might be about a hundred years old which turns out to be a popular photography subject.

During Reza Shah Pahlavi, Niavaran palace was abandoned until Mohammad Reza went married and the young couple decided to live here, however it did not take long.

During Mohammad Reza reign, this building was used as the residence of the crown prince, Reza, after restoration and some changes in decoration by a group of French designers.

Ahmad Shahi pavilion was closed for ten years after the revolution, until 1989 which was open to the public, following a recovery. Today, the pavilion is one of the most outstanding buildings in Niavaran palace. Reza’s properties including his stone collection and model planes impress many visitors.

Jahan Nama Museum

Jahan Nama is a museum in Niavarn which was added to the complex in 1977 to host the international gifts of Farah Diba, the queen, and also the various objects she had bought from different parts of the world. Today, ancient objects of great civilizations are displayed in this museum. Among these, works of distinguished artists of 20th century such as Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Marc Chagall, George Braque, Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Gauguin and many contemporary Iranian artists are remarkable.

Private Library

On the northeast of Niavaran complex, there is a two-floor building including a basement, altogether with an area of 770 meters, dating back to 43 years ago to be served as a private library. The interior design had been completed by Aziz Farmanfarmayan, design and composition of glass and mirrors has been done by American artist, Charles Sevigny.

The library lacks general standards of a library, since it was built as a private library. Evidence such as the piano and sound equipment shows that the place was used as a music room as well. Using elements of interior design like paintings, furniture and statues has given the atmosphere of a museum to the places.

There are about 23000 volumes of books including 16000 Persian books and some from non-Iranian authors. Excellent travelogues written by famous people traveling to Asia and Iran, collection of paintings particularly by artists of 20th century are only parts of these prosperous library.

Museum of Royal Family’s Vehicles

In 2011, Iranian authorities decided to make a collection of royal family vehicles in Niavaran palace. A few months later the museum, was open to visitors, following particular aims:

- Displaying vehicles to the public

- Organizing vehicles of the collection

- Optimizing conservation system and protecting the heritage

- Attracting more visitors

The construction allocated to vehicle museum covers an area of 200 square meters. However, being used as garage, it lacks decorative arts. Rather than being worked as a specialized museum, the focus is on conservation of royal family vehicles as a national treasure and historical storytelling.

Two Rolls Royce Phantom 5 and 6 are displayed right in the middle of the hall, surrounded by Formula racing car and eight motorcycles belonged to royal family children. Looking around, you can also see some maquettes in this gallery and some photos of the royal family with these vehicles.

Museum of Royal Clothes & Fabrics

The first glance at this gallery, brings to mind the harmony of Iranian clothes with beauty of nature and surrounding environment. It also presents Iranian artists’ skill in textile production.

The museum of clothes is one of the permanent treasures of the complex.

Niavaran palace Opening hours

The complex is open to visitors, Monday to Sunday from 9 am to 7 pm during spring and summer and from 8 am to 5 pm during fall and winter. To buy the ticket, visitors should arrive there an hour before the closing time.

On important national holidays, the complex is closed. So, do not forget to check before visiting.

How to arrive to Niavaran Palace

If you are looking for public transport rout, you have to get to Tajrish metro station, on Line 1, then take a cab to Niavaran square, it is a five-minute walk to the palace.

Another possible option would be “Tap30”, either from Tajrish metro station or anywhere you are in Tehran. It is quite affordable, however trying public transportation would save your money.

Niavaran palace café and restaurant

Imagine sitting in a restaurant surrounded by tall trees, only 500 meters from a historical building! If you like the peaceful atmosphere, then you are welcomed to have a drink or food in “Karzin” cafe and restaurant. However, on the weekends and holidays you should expect some crowd. The café is famous for its brunch, the brunch buffet is open until 1 PM.

Opening hours

Spring and summer: Every day from 9:00 a.m. to 18:00 p.m. except public mourning holidays

Fall and winter: Every day from 8:00 a.m. to 16:00 p.m. except public mourning holidays