Naqsh-e Rustam, the Ancient Necropolis of Powerful Persian Kings

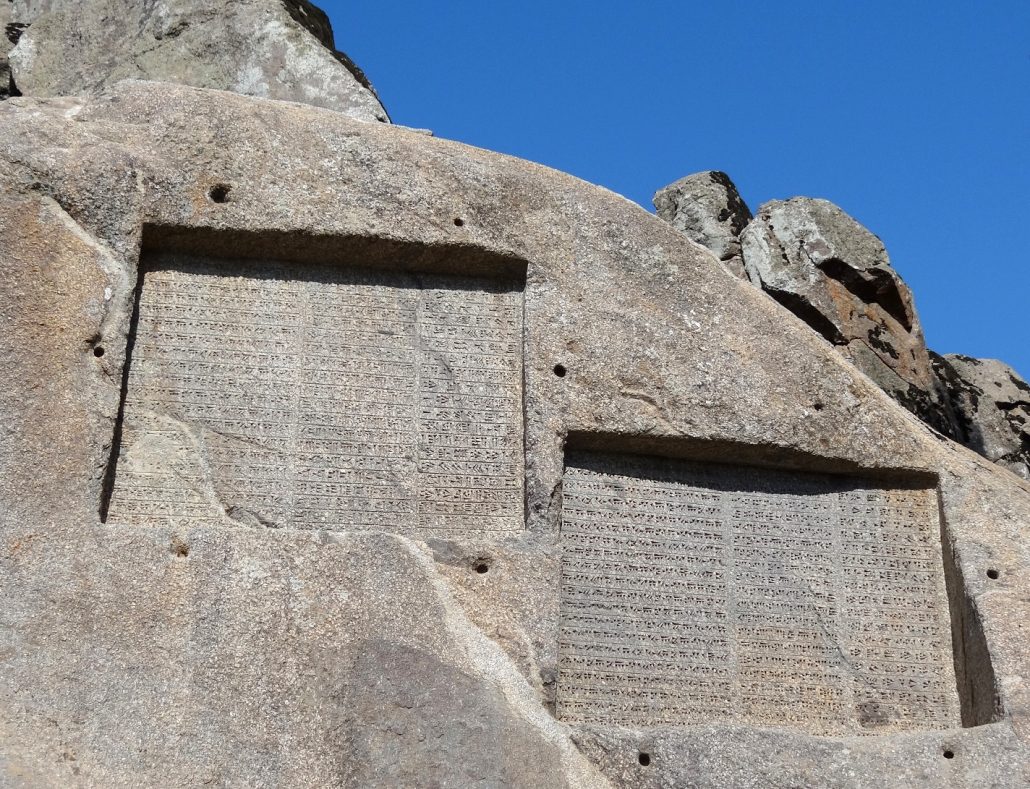

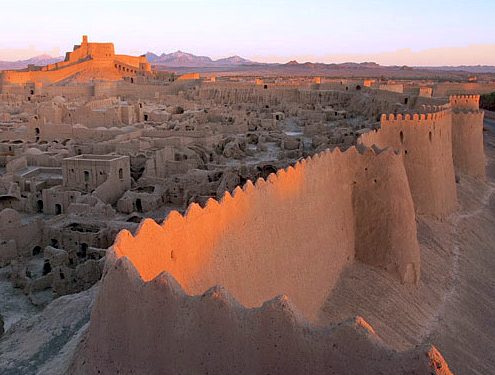

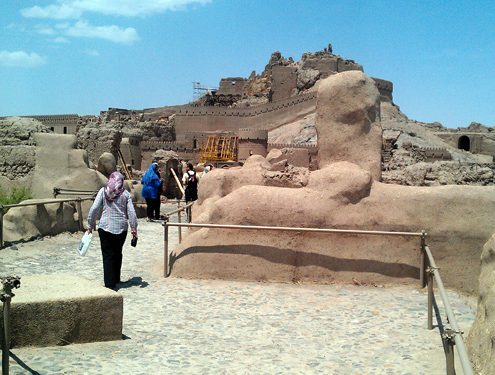

Naqsh-e Rustam is an ancient necropolis situated northwest of Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Naqsh-e Rustam (Naqsh-e Rostam) is an impressive reminder of once glorious Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BC) and it stands as a magnificent manifestation of ancient Persian art. Naqsh-e Rustam is the house for the immense rock tombs cut high into the cliff. The rock tombs belong to four Achaemenian kings. The ancient tombs attracted Sasanian kings as well. They wished to imitate the glory of the Achaemenian kings; maybe that is why they created huge reliefs besides the tombs. The immense rock reliefs mainly depict the investiture scenes and the equestrian fights of the Sasanian kings. However, the history of Naqsh-e Rustam is not limited to the Achaemenid and Sassanid periods. There is evidence that the site exists from the Elamite period. An ancient rock relief dating back to Elamite period indicates that Naqsh-e Rustam had been a sacred place during the ancient times. That might be the reason Darius I ordered to carve his monumental tomb into the cliff at the foot of Mt. Hosain (Huseyn Kuh). His rock tomb is famous for its two inscriptions known as the king’s autobiography. The inscriptions indicate that Darius the Great had been the king who ruled according to justice. Travel to Iran and enjoy visiting so many great cultural attractions especially the great ones registered on UNESCO World Heritage List or waiting to be registered. Pasargadae, Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rajab that lies a few hundred meters from Naqsh-e Rustam, and Naqsh-e Rustam, the ancient necropolis of the powerful Persian kings are the best cultural attractions of Iran located in Shiraz, Fars province,.

Achaemenid Tombs

Naqsh-e- Rustam houses four rock tombs carved out of rock face. Since the façades of the four Achaemenian tombs look like Persian crosses- chalipa- some call it Persian Crosses as well. The entrance to each tomb is located at the center of the cross and it leads to a small chamber where the king’s body lay in a sarcophagus. It is not clear whether the bodies were directly put into the sarcophaguses or the bodies were exposed to a tower of silence, and then the bones were put there. What is certain is that the tombs were closed after the burial, but the doors were smashed and the tombs were looted after the invasion of Alexander the Great in the 4th BC.

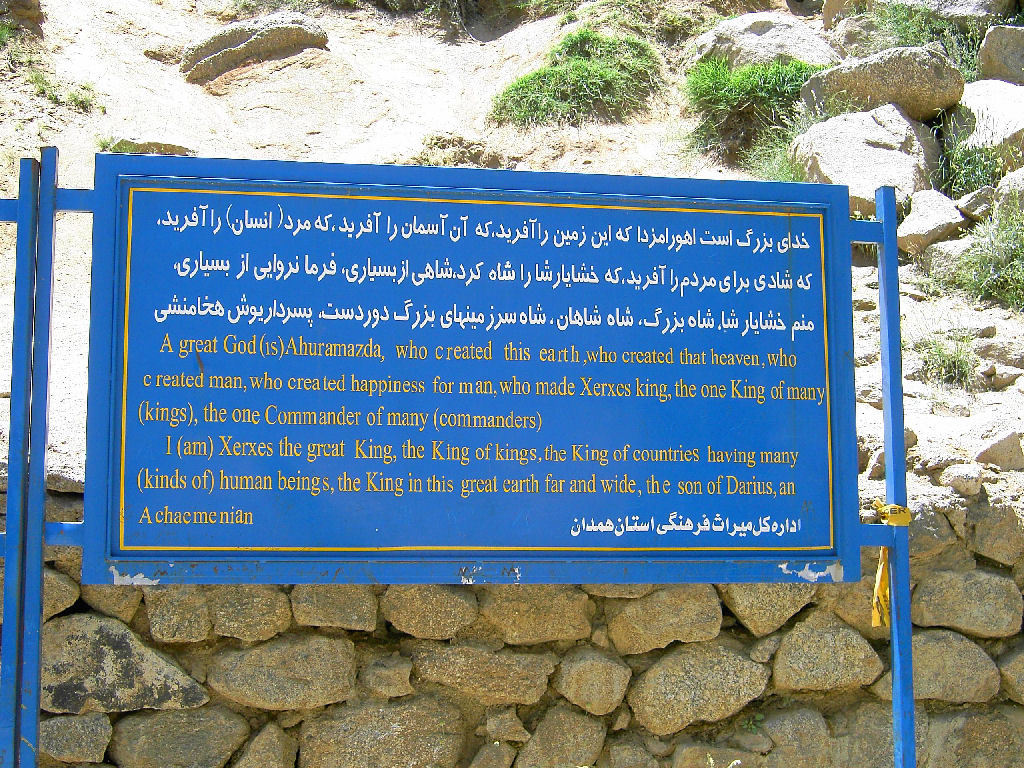

Ka’ba-ye Zartosht

In front of the rock tombs, there is a square tower known as the Ka’ba-ye Zartosht that means the Cube of Zoroaster (Ka’ba is the famous monument as a holy site for Muslims located in Mecca). The structure of the building is a copy of a sister building at Pasargadae known as the Prison of Solomon; however, this building is a few decades older than Ka’ba-ye Zartosht. On the wall of the tower, there is an inscription in three languages from Sasanian time and it is considered as one of the most important inscriptions of that period. It is not obvious what the purpose of the building had been. It might have been a library for the holy books, a place to keep the holy fire, or maybe a treasury.

According to Persepolis fortification tablets, there must have been trees at Necropolis that apparently it refers to Naqsh-e Rustam. The experts believe that there must have been three lines of trees in the area between the tower and the tombs; however, it has been a long time since the trees have disappeared.

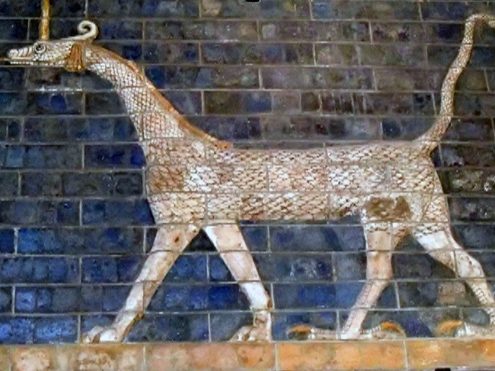

Sassanid Reliefs

Besides the tombs, there are seven over-sized stone reliefs dating from the 3rd century AD. The huge rock reliefs mainly belong to the Sassanid period and they depict scenes of imperial conquests and royal ceremonies. What is amazing about the reliefs is that they indicate details of events carved in the heart of rough rocks. Therefore, they can give the visitors a visual insight into the spirits of the ancient times.

The most famous rock relief at Naqsh-e Rustam belongs to the Sasanian king Shapur I. The relief depicts his victory over two Roman emperors; Valerian and Philip the Arab. Shapur I is on the horseback, while Valerian is bowing to him and Philip the Arab is holding Shapur’s horse.

The investiture relief of Ardashir I as the founder of the Sassanid Empire is also depicted. The relief indicates Ohrmazd giving Ardeshir the ring of kingship. The inscription also has the oldest use of the term “Iran”.

There are also the equestrian reliefs such as equestrian relief of Hormizd II at Naghsh-e Rustam. The relief depicts Hormozid and above the relief, one would see a badly damaged relief that apparently is depicting Shapur II with his courtiers.

The relief of Bahram II depicts the king with an oversized sword. On the left, five figures stand and they seem to be the members of the king’s family. On the right, three courtiers stand and one of them is apparently Kartir- a highly prominent Zoroastrian priest.

The Oldest Relief at Naqsh-e Rustam

The oldest relief at Naqsh-e Rustam dates back to approximately 1000 BC and it dates back to the Elamite period. Though the relief is severely damaged, it depicts a faint image of a man with an unusual head-gear. He is thought to be an Elamite one.

Why Is It Called Naqsh-e Rustam?

Sassanid reliefs mainly depict equestrian fights or investiture scenes. Since the equestrian fights of the Sasanian kings represent the tales of chivalry, locals believed that the man depicted on reliefs was Rustam, the hero of Shahnameh. The epic of Shahnameh is the masterpiece of Ferdowsi, the great Iranian poet of the 10th and 11th the century. Therefore, the site is called Naqsh-e Rustam (meaning the carvings of Rustam); because the locals believed that the carved man on the reliefs was their epic hero” Rustam”.