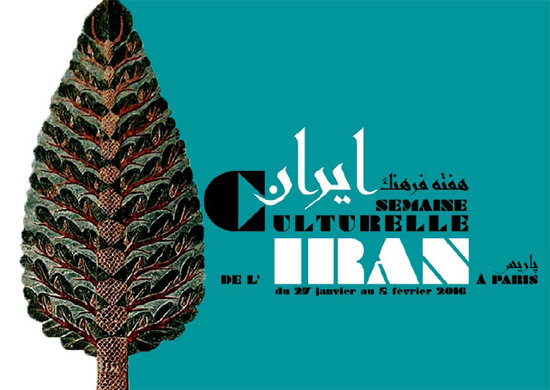

Iranian Handicrafts Exhibition in Paris

Iranian Handicrafts Exhibition in Paris

|

Concurrent with the visit of President Rouhani to France, Paris will host Iran’s cultural week and open an Iranian handicraft exhibition, Deputy Head of Cultural Heritage said.

Deputy Head of Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (ICHTO) Bahman Namvar Motlagh told MNA correspondent that coinciding with President Rouhani’s visit to France, Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization in collaboration with Iranian Embassy in France, will hold various programs during Iran’s cultural week, saying this is the first time a political visit has been entwined with culture. “As a cultural country, we have planned to hold an exhibition in Paris municipality showcasing 150 items of unique and highly valuable Iranian handicrafts,” he said. According to Namvar Motlagh, the exhibition aims to promote and introduce Iranian handicraft to French people, although all items can be ordered for purchase. He went on to add that a number of paintings of Iran’s historical sites and monuments will be also put on display. Iran’s cultural week will be officially inaugurated in Paris on Thursday, 28 January. In addition to handicrafts exhibition, there will be a number of programs on Iranian cinema and music.

Iran is home to one of the richest art heritages and handicrafts in world history and distinguished in many disciplines,

|

| Rytone- The Art of Achaemenids |

including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and stone masonry. Persians were among the first to use mathematics, geometry, and astronomy in architecture and also have extraordinary skills in making massive domes which can be seen frequently in the structure of bazaars and mosques. Iran, besides being home to a large number of art houses and galleries, also holds one of the largest and valuable jewel collections in the world.

The art of carpet weaving in Iran dates backs to 2,500 years and is rooted in the culture and customs of its people and their instinctive feelings. Weavers mix elegant patterns with a myriad of colors. The Iranian carpet is similar to the Persian garden: full of florae, birds and beasts. The colors are usually extracted from wild flowers, and are rich in colors such as burgundy, navy blue and accents of ivory. The proto-fabric is often washed in tea to soften the texture, giving it a unique quality. Depending on where the rug is made, patterns and designs vary. Some rugs such as Gabbeh, and Kilim have variations in their textures and number of knots as well. Out of about 2 million Iranians involved in the trade, 1.2 million are weavers who produce the largest amount of hand-woven carpets in the world.

Oriental historian Basil Gray believes “Iran has offered a particularly unique art to the world which is excellent in its kind”. Caves in Iran’s Lorestan province exhibit painted imagery of animals and hunting scenes. Those in Fars province and Sialk are at least 5,000 years old. Painting in Iran is thought to have reached a peak during the Tamerlane era when outstanding masters such as Kamaleddin Behzad gave birth to a new style of painting. Qajarid paintings, for instance, are a combination of European influences and Safavid miniature schools of painting such as those introduced by Reza Abbasi. Masters such as Kamal-ol-Molk further pushed forward the European influence in Iran. It was during the Qajar era when “Teahouse painting” emerged. Subjects of this style were often religious and nationalist in nature depicting scenes from Shiite history and literary epics like Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh.

A Persian miniature is a richly detailed miniature painting which depicts religious or mythological themes from the region of

|

the Middle East now known as Iran. The art of miniature painting in Persia flourished from the 13th through the 16th centuries, and continues to this day, with several contemporary artists producing notable Persian miniatures. These delicate, lush paintings are typically visually stunning, with a level of detail which can only be achieved with a very fine hand and an extremely small brush. Persian miniature is a small painting, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, which probably had an influence on the origins of the Persian tradition. Although there is an equally well-established Persian tradition of wall painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West. Several features about Persian miniatures stand out. The first is the size and level of detail; many of these paintings are quite small, but they feature rich, complex scenes which can occupy a viewer for hours. Classically, a Persian miniature also features accents in gold and silver leaf, along with a very vivid array of colors. The perspective in a Persian miniature also tends to be very intriguing, with elements overlaid on each other in ways which sometimes feel awkward to people who are accustomed to the look and feel of Western art.

Prominent archeologist Roman Ghirshman said, “The taste and talent of these people [Iranians] can be seen through the designs of their earthenware.” Of the thousands of archeological sites and historical ruins of Iran, almost every one of them can be found to have been filled, at some point, with earthenware of exceptional quality. Thousands of unique vessels alone were found in Sialk and Jiroft sites. The occupation of the potter (kouzehgar) has a special place in Persian literature.

Persian calligraphy has several styles. The style initiated by Darvish was emulated by his contemporaries–Mirza Hassan

|

Isfahani, Mirza Kouchek Isfahani and Mohammad Ali Shirazi. After his death, the Shekasteh style fell into stagnation until it was revived in the 1970s. Says writer Will Durant: “Ancient Iranians, with an alphabet of 36 letters, used skins and pen to write instead of earthen tablets.” Such was the creativity spent on the art of writing. The significance of the art of calligraphy in works of pottery, metalwork and historical buildings is such that they are considered deficient without the calligraphic adorning. Illuminations, especially in the Qur’an and works such as Shahnameh, Divan-e Hafez, Golestan and Boustan, are recognized as highly invaluable because of their delicate calligraphy alone. Vast quantities of these are scattered and preserved in museums and private collections worldwide such as the Hermitage Museum of St. Petersburg and Washington’s Freer Gallery of Art among many others.

Tilework is a unique feature of the blue mosques of Isfahan. In the old days, Kashan (kash + an literally means “land of tiles”) and Tabriz were famous centers of Iranian mosaic and tile industry in the past. Since centuries, Iranian art has developed particular patterns to decorate Iranian crafts. These motifs can be: – Inspired by ancestral nomad tribes (such as geometrical motifs used in kilims or gabbehs). – Islam influenced, with an advanced geometrical research. – Oriental based, also found in India or Pakistan.

|

Delicate and meticulous marquetry has been produced since the Safavid period. In fact, khatam was so popular in the court that princes learned this technique alongside music and painting. Khatam means incrustation and Khatamkari refers to incrustation work. This craft consists in the production of incrustation patterns (generally star shaped) with thin sticks of wood (ebony, teak, zizyphus, orange, rose), brass (for golden parts) and camel bones (white parts). Ivory, gold or silver can also be used for collection objects. Sticks are assembled in triangular beams, themselves assembled and glued in a strict order to create a cylinder 70 cm in diameter, whose cross-section is the main motif: a six-branch star included in a hexagon. These cylinders are cut into shorter cylinders, and then compressed and dried between two wooden plates, before being sliced for the last time, in 1 mm wide trenches. These sections are ready to be plated and glued on the object to be decorated, before lacquer finishing. The trench can also be softened through heating in order to wrap around objects. Many objects can be decorated in this fashion, such as jewelry/decorative boxes, chessboards, pipes, desks, frames or some musical instruments. Khatam can also be used in Persian miniatures, making it a more attractive work of art. Based on techniques imported from China and improved by Persian know-how, this craft has existed for more than 700 years and is still practiced in Shiraz and Isfahan.

|

Enamel working and decorating metals with colorful and baked coats are one of the distinguished artwork in Isfahan.

Although this course is of abundant use industrially for producing metal and hygienic dishes, it has been paid high attention by painters, goldsmiths and metal engravers since a long time. Worldwide, it is categorized as follows: 1- Enamel painting 2- Charkhaneh or chess- like enamel 3- Cavity enamel. Enamel painting is practiced in Isfahan and specimens are kept in the museums of Iran and abroad, indicting that Iranian artists have been interested in this art and used it in their metalwork ever since the rule of Achaemenian and Sassanid dynasties. Since enamels are delicate, we do not have many of them left from ancient times. Some documents indicate that throughout the Islamic civilization of and during the Seljuk, Safavid and Zand dynasties, there have been outstanding enameled dishes and materials. Most of the enameled dishes related to the past belong to the Qajar dynasty during 1810–90. Bangles, boxes, water-pipe heads, vases and golden dishes with beautiful paintings in blue and green colors remain from that time. This art stagnated for 50 years due to World War I and the social revolution. However, this art was fostered in terms of quantity and quality by Master Shokrollah Saniezadeh, the outstanding painter of Isfahan, for 40 years. Since 1992, this art has begun to thrive after many distinguished artists began working in this field.

Ghalamkar (Qalamkaar, also qalamkar, kalamkar) fabric is a type of Textile printing, patterned Iranian Fabric. The fabric is printed using patterned wooden stamps. It is also known as Kalamkari in India which basicaly is a type of hand-painted or block-printed cotton textile.

|

Termeh is a handwoven cloth of Iran, primarily produced in the Yazd province. Weaving Termeh requires a good wool with tall fibers. Termeh is woven by an expert with the assistance of a worker called “Goushvareh-kesh”. Weaving Termeh is a sensitive, careful, and time-consuming process; a good weaver can produce only 25 to 30 centimeters in a day. The background colors which are used in Termeh are jujube red, light red, green, orange and black. Termeh has been admired throughout history: Greek historians commented on the beauty of Persian weavings in the Achaemenian (532 B.C.), Ashkani (222 B.C.) and Sasanidae (226-641 A.D.) periods and the famous Chinese tourist Hoang Tesang admired Termeh. After Islam’s arrival in Iran, the Persian weaving arts were greatly developed, especially during the Safavie period (1502-1736 A.D.), during which time Zarbaf and Termeh weaving techniques were both significantly refined. Due to the difficulty of producing Termeh and the advent of mechanized weaving, few factories remain in Iran that produce traditionally woven Termeh. Rezaei Termeh is the most famous of the remaining factories.

|

| Termeh |

Kilims are flat tapestry-woven carpets or rugs produced from the Balkans to Pakistan. Kilims can be purely decorative or can function as prayer rugs. Recently made kilims are popular floor-coverings in Western households. Kilims are produced by tightly interweaving the warp and weft strands of the weave to produce a flat surface with no pile. Kilim weaves are tapestry weaves, technically weft-faced plain weaves, that is, the horizontal weft strands are pulled tightly downward so that they hide the vertical warp strands. When the end of a color boundary is reached, the weft yarn is wound back from the boundary point. Thus, if the boundary of a field is a straight vertical line, a vertical slit forms between the two different color areas where they meet. For this reason, most kilims can be classed as “slit woven” textiles. The slits are beloved by collectors, as they produce very sharp-etched designs, emphasizing the geometry of the weave. Weaving strategies for avoiding slit formation, such as interlocking, produce a more blurred design image. The weft strands, which carry the visible design and color, are almost always wool, whereas the hidden warp strands can be either wool or cotton. The warp strands are only visible at the ends, where they emerge as the fringe. This fringe is usually tied in bunches, to ensure against loosening or unraveling of the weave.