A motorcycling adventure across Iran: ‘the standout attraction is the people’ | Travel

In the dining room of a remote hotel in Iran’s Alborz Mountains was a locked glass case displaying a solitary English-language book.The Valleys of the Assassins, Freya Stark,” said the hotelier as he unlocked the case, removed the book and turned to the page of a hand-drawn map. He pointed to our location. “You know Freya Stark? She came here in 1930. English lady, like you.” I nodded. She was one of the reasons for my journey.

“I think you are Freya Stark – but on motorcycle!” he declared as he carefully returned the book and locked the cabinet door. It seemed like a lot of reverence for a 10-quid paperback, but the book has immortalised this valley and his village.

I was motorcycling through the Alborz as part of a longer ride around Iran. My journey would take me more than 3,000 miles from the Turkish border to the southern deserts. I had long been an admirer of the British explorer and author and her forays into 1930s Persia, which she approached with a gung-ho attitude not normally associated with the serious geographical expeditions of the era. Most of all, I liked that she was entirely unpretentious about her motivation. “For my own part I travel single-mindedly, for fun,” she said.

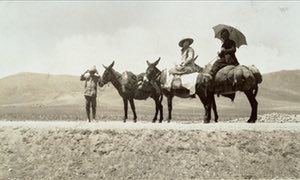

Stark had walked this same route I was riding more than 80 years earlier, tackling dangerous terrain and doubting locals in order to map what was then uncharted territory. She was on a mission to discover the ruins of Alamut Fortress, headquarters of the ancient Ismaili sect, better known as the Hashashin, who had terrorised this region in the 11th century.

Even today, the steep-sided mountain roads of the Alborz have a lonely, forbidding feel, but here, and throughout Iran, I would find myself approached at the roadside by complete strangers who would invite me to stay at their homes. The feeding would begin as soon as I walked through the door – plates of fresh melon, sweets and nuts served with tea – always tea. Meals of flatbread and yogurt dips followed by stews, on piles of Persian tahdig rice – crisped on the bottom of the pan and drenched in butter. I asked one man about Iranian hospitality. “People must look after each other,” he told me, with a serious expression. “No matter what religion we are.”

Although I set off on this journey carrying my camping gear, my tent remained unpitched. With each host, I was passed on to their friends and relatives throughout the country, all seemingly happy to host a strange British woman on a motorcycle. Occasionally I would crave the anonymity of a hotel room. In larger towns there was always a small guesthouse where I could relax.

Although the southern slopes of the Alborz are close enough to Tehran to offer ski-resorts and hiking trails, in the more isolated valleys the weather can change quickly and navigation becomes challenging. But for a motorcyclist on a trail bike, the Alborz are a paradise of dirt tracks and waterfalls, where eagles circle high above jagged black rock and snow-capped peaks.

Stark encountered her share of obstacles when she set out to explore this region, but it was a different set of challenges to those a British woman faces today, travelling alone in the Islamic Republic of Iran. In the 1930s Persia was ruled by the secular Reza Shah, who was actively modernising the country, including emancipating the female population – to the extent of banning the hijab. The British presence also remained powerful, running Iran’s oil industry, railways and telecommunications.

Eight decades, one MI6-backed coup and an Islamic revolution later, it remains a challenge for a solo British woman to enter Iran, especially on a motorcycle – a form of transport outlawed for Iranian women. But after some interrogation, fingerprinting and a little skulduggery on my part, I made it across the border. Like so many Brits before me, my fascination soon turned into full-blown Persophilia. The sheer otherness of Iran is enchanting – wandering through the 15th-century bazaar in Tabriz, piled high with saffron, gold and carpets, or exploring the ruins of Persepolis, the seat of Persia’s ancient kings.

A guidebook will point you to the glittering mosques, palaces and ancient gardens, but Iran’s standout attraction is its people. Travelling by motorcycle made for easy icebreaking, but on my few excursions by public transport I experienced the same eager hospitality and appetite for spirited conversation, laughter and human connection.

I made my journey in 2013 and the following year Iran forbade British citizens from travelling independently, so the only way to go was with an authorised tour or guide. Last year the British embassy in Tehran reopened and travel restrictions were lifted, making Iran more accessible than it has been for years. I have returned to Iran each year since my first trip and its allure never dulls. The deeper I dig, the more intrigued and enamoured I become. If you have a chance to see Iran, take it. I am so glad I did.