Iran World Heritage Sites

Persepolis:

Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 550–330 BC). It is situated 60 km northeast of the city of Shiraz in Fars Province, Iran. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

The site includes a 125,000 square meter terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Rahmet Mountain. The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which vary in height with the slope of the ground. Rising from 5–13 meters (16–43 feet) on the west side was a double stair. From there, it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. André Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but that it was Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces.

Since, to judge from the inscriptions, the buildings of Persepolis commenced with Darius I, it was probably under this king, with whom the scepter passed to a new branch of the royal house, that Persepolis became the capital of Iran proper. As the residence of the rulers of the empire, however, a remote place in a difficult alpine region was far from convenient. The country’s true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This accounts for the fact that the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

Darius I ordered the construction of the Apadana and the Council Hall (Tripylon or the “Triple Gate”), as well as the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire.

Around 519 BC, construction of a broad stairway was begun. The stairway was initially planned to be the main entrance to the terrace 20 meters (66 feet) above the ground. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan Stairway, was built symmetrically on the western side of the Great Wall. The 111 steps measured 6.9 meters (23 feet) wide, with treads of 31 centimeters (12 inches) and rises of 10 centimeters (3.9 inches). Originally, the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback. New theories, however, suggest that the shallow risers allowed visiting dignitaries to maintain a regal appearance while ascending. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of All Nations.

Grey limestone was the main building material used at Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, the terrace was prepared. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain. Professor Olmstead suggested the cistern was constructed at the same time that construction of the towers began.

The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Diodorus Siculus writes that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide a protected space for the defense personnel. The first wall was 7 meters (23 feet) tall, the second, 14 meters (46 feet) and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27 meters (89 feet) in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

Persepolis-Iran-Shiraz

Naqsh-e Jahan Square:

Naghsh-e-Jahan Square is a huge rectangular square in Isfahan, Iran, which is surrounded by monuments from Safavid period. Naghsh-e-Jahan Square was built during the reign of Safavid Shah Abbas. There are other historical monuments in the square including Ali Qapu Palace, Imam Mosque, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Qeisarieh Gate. In addition to these monuments, there are 200 chambers around the square, in which Isfahan’s handicrafts are presented.

In comparison with “Place de la Concorde” in Paris, Naghsh-e-jahan Square is historically superior, and after “Tiananmen Square” in Beijing, it is the second largest square in the world.

Due to the harmony existing in the construction of it, Naghsh-e-Jahan Square has surprised Europeans during centuries.

The square was registered in Iran’s National Heritage on January 28, 1935 under the registration number of 102. Also, it was among the first Iranian monuments, which was registered in UNESCO World Heritage in April, 1979 under the registration number of 115.

The square was named “Shah Square” after it was built, and it was registered in World Heritage list under this name. Currently, however, it is also known as “Imam Square” in that list.

Naqsh-e Jahan

Yazd city:

Yazd city is the center of Yazd province, Yazd is considered to be of the old cities of Iran and one of the best desert cities. It’s the first raw adobe city and the second historical city in the world after Venice in Italy. This region has been considered as one of the main and historical path and passageways of Iran and has always been noted by governments. Yazd is known as the “City of Wind Tower”. Also, “Bride of the Desert”, “Dar al Elm”, “City of Bicycles” and “the City of Sweets” are considered to be its other titles. Yazd is the city of different cultures and religions and its cultural inhabitants live peacefully together. This city is sister to the cities of Homs in Syria, Jaszbereny in Hungary, Nizwa in Oman, Jakarta the capital of Indonesia, Holguin in Cuba and Yeosu in South Korea.Yazd city was Just registered in UNESCO World Heritage in July, 2017

Yazd city

Tabriz Bazaar:

The Bazaar of Tabriz (Romanized as Bāzār-e Tabriz) is a historical market situated in the city center of Tabriz, Iran. It is one of the oldest bazaars in the Middle East and the largest covered bazaar in the world. [Citation needed] and is one of Iran’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Tabriz has been a place of cultural exchange since antiquity. Its historic bazaar complex is one of the most important commercial centers on the Silk Road. A bazaar has existed on the same site since the early periods of Iranian urbanism following Islam.

Located in the center of the city of Tabriz, Iran, the structure consists of several sub-bazaars, such as Amir Bazaar (for gold and jewelry), Mozzafarieh (a carpet bazaar, sorted by knot size and type), shoe bazaar, and many other ones for various goods such as household items. The most prosperous time of Tabriz and its bazaar was in the 16th century when the town became the capital city of the Safavid kingdom. The city lost its status as a capital in the 17th century, but its bazaar has remained important as a commercial and economic center. Although numerous modern shops and malls have been established nowadays, Tabriz Bazaar has remained the economic heart of both the city and northwestern Iran.

Tabriz Bazaar has also been a place of political significance, and one can point out its importance in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution in the last century and Islamic Revolution in the contemporary time.

The bazaar was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in July 2010.

Tabriz-bazaar

Traditional water sources of Persian antiquity (Qanat):

Most rivers in Iran are seasonal and have traditionally not been able to supply the needs of urban settlements. Major rivers like the Arvand, Aras, Zayandeh, Sefid and Atrak were few and far between in the vast lands of Persian antiquity.

With the growth of urban settlements during the ages, locally dug deep wells (up to 100 meters deep) could no longer keep up with the demand, leading to the systematic digging of a specialized network of canals known as Qanat.

Persia’s Qanat system dates back many centuries, and thousands of years old. The city Zarch in central Iran has the oldest and longest qanat (over 3000 years and 71 km long) and other 3000 years old qanats have been found in northern Iran. The Qanats mostly came in from higher elevations, and were split into a distributing network of smaller underground canals called Kariz when reaching the city. Like Qanats, these smaller canals were below ground (~20 steps), and were built such that they were very difficult to contaminate. These underground aqueducts, built thousands of years ago suffer no evaporation loss and are ideally suited for drinking water since there is no pollution danger.

But with the further growth of the city in Persian lands, even the Qanats could not respond to the needs of residents. That is when some wealthy inhabitants started building private reservoirs called Ab Anbar.

This Qanat surfacing in Fin is from a spring thought to be several thousand years in running, called The Spring of Solomon (“Cheshmeh-ye Soleiman”). It is thought to have been feeding the Sialk area since antiquity.

In the middle of the twentieth century, it is estimated that approximately 50,000 qanats were in use in Iran, each commissioned and maintained by local users. Of these only 25,000 remain in use as of 1980.

One of the oldest and largest known qanats is in the Iranian city of Gonabad which after 2700 years still provides drinking and agricultural water to nearly 40,000 people. Its main well is more than 360 meters deep and the qanat is 45 kilometers long. Yazd, Khorasan and Kerman are the known zones for their dependence with an extensive system of qanats.

In traditional Persian architecture, a Kariz is a small Qanat, usually within a network inside an urban setting. Kariz is what distributes the Qanat into its final destinations.

Qanats of Gonabad also is called kariz Kai Khosrow is one of the oldest and largest qanats in the world built between 700 BC to 500 BC. It is located at Gonabad, Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran. This property contains 427 water wells with total length of 33113 meters. This site were first added to the UNESCO’s list of tentative World Heritage Sites in 2007, then officially inscribed in 2016 with several other quants under the World Heritage Site name of “The Persian Qanat.

Qanat

Shushtar:

Shushtar is located in Khuzestan province. This region is situated on the slope of Zagros mountains and has unparalleled historical and tourist attractions. This county is known as one of the most important tourist areas of Iran and its mills and hydraulic systems, which have been registered in World Heritage, attracts many Iranian and foreign tourists.

shushtar-historical-hydraulic-system

Susa:

Susa is of the northern counties of Khuzestan province and its center is the city of Susa. The ancient Susa city has been of the centers of old civilization, of the most famous cities in the world, several thousand year old capital of Elam civilization and also the winter capital of the Achaemenian empire. Of its valuable historical monuments Chogha Zanbil ziggurat and the historical site of Susa can be mentioned; which are all registered as world heritage. Susa county, due to its special geographical location and valuable and unique historical and religious monuments, has a special place in the area of tourism

Susa

Gonbad-e Qabus Tower:

Tower of Gonbad-e Kabus is a historical and glorious construction and it is one of the attractions of Gonbad-e Kabus town in Gulistan province and it is located in a vast and beautiful park and attracts the eye of any observer from kilometers long. The Tower of Gonbad-e Kabus is a valuable relic left from the fourth Hijri century and is a remnant of Ziyarid dynasty in this land of Iran. This tower used to be the guide and landmark of travelers who used to pass this land. Tower of Gonbad-e Kabus is the largest brick tower of Iran and is one of the longest towers of the world.

Tower of Gonbad-e Kabus was registered in the 36th UNESCO conference as a world heritage.

Gonbad-e Qabus Tower

Jameh Mosque, Isfahan:

Isfahan is one of the famous cities in the world due to its ancient history and numerous ancient monuments. According to Andre Malraux, it is only comparable to two cities of Beijing and Florence. The major part of this city is related to the period after the advent of Islam, especially Seljuks and Safavid eras and precious monuments have remained among the mosques, inns, squares, bridges and streets from those periods.

Isfahan has sister city relationship with ten cities of Freiburg in Germany, Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, Florence in Italy, Xi’an in China, St. Petersburg in Russia, Havanna in Kuba, Yash in Romania, Kuwait City and Barcelon in Spain.

Jom’e Mosque or Jameh Mosque of Isfahan is one of the most important and oldest religious monuments in Iran. This mosque presents a vast historical complex of 170 × 140 meters in dimension in the north east of Isfahan and beside the old square and today it includes different parts such as Nezam al-Molk Dome, Taj ol-Molk Dome, four-porch yard and its circle chambers, Mozaffari School and Aljayto Altar, each of which represents the process of Islamic architecture over different periods. Architecture of this mosque is admirable and it has a unique altar. Based on historical evidences, Jameh Mosque of Isfahan has been built on the ruins of an even older mosque which was built in Judea by resident Arabs of Tehran in the second Hijri century. The first mosque was established on the ruins of buildings related to the late Sassanid period.

The most important development plans took place in Buyids and Safavid era. The architecture of the mosque is in Razi Style. Jameh Mosque of Isfahan reflects Byzantine and classic art in the form of a traditional and Islamic building.

This mosque is one of the monuments registered in UNESCO World Heritage.

Jameh Mosque

Pasargadae:

Pasargadae was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great who had issued its construction (559–530 BC); it was also the location of his tomb. It was a city in ancient Persia, located near the city of Shiraz (in Pasargad County), and is today an archaeological site and one of Iran’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Cyrus the Great began building the capital in 546 BC or later; it was unfinished when he died in battle, in 530 or 529 BC. The remains of the tomb of Cyrus’ son and successor Cambyses II have been found in Pasargadae, near the fortress of Toll-e Takht, and identified in 2006.

Pasargadae remained the capital of the Achaemenid Empire until Cambyses II moved it to Susa; later, Darius founded another in Persepolis. The archaeological site covers 1.6 square kilometres and includes a structure commonly believed to be the mausoleum of Cyrus, the fortress of Toll-e Takht sitting on top of a nearby hill, and the remains of two royal palaces and gardens. Pasargadae Persian Gardens provide the earliest known example of the Persian chahar bagh, or fourfold garden design (see Persian Gardens).

The Gate R, located at the eastern edge of the palace area, is the oldest known freestanding propylaeum. It may have been the architectural predecessor of the Gate of All Nations at Persepolis.

Pasargadae

Arg-e Bam:

The Arg-e Bam was the largest adobe building in the world, located in Bam, a city in Kerman Province of southeastern Iran. It is listed by UNESCO as part of the World Heritage Site “Bam and its Cultural Landscape”. The origin of this enormous citadel on the Silk Road can be traced back to the Achaemenid Empire (sixth to fourth centuries BC) and even beyond. The heyday of the citadel was from the seventh to eleventh centuries, being at the crossroads of important trade routes and known for the production of silk and cotton garments.

The entire building was a large fortress containing the citadel, but because of the impressive look of the citadel, which forms the highest point, the entire fortress is named the Bam Citadel.

On December 26, 2003, the Citadel was almost completely destroyed by an earthquake, along with much of the rest of Bam and its environs. A few days after the earthquake, the President of Iran, Mohammad Khatami, announced that the Citadel would be rebuilt.

Arg-e Bam

Takht-e Soleyman:

Takht-e Soleyman, also known as Azar Goshnasp, literally “the Fire of the Warrior Kings”, is an archaeological site in West Azarbaijan, Iran. It lies midway between Urmia and Hamadan, very near the present-day town of Takab, and 400 km (250 mi) west of Tehran.

The originally fortified site, which is located on a volcano crater rim, was recognized as a World Heritage Site in July 2003. The citadel includes the remains of a Zoroastrian fire temple built during the Sassanid period and partially rebuilt during the Ilkhanid period. This site got this Semitic name after the Arab conquest. This temple housed one of the three “Great Fires” or “Royal Fires” that Sassanid rulers humbled themselves before in order to ascend the throne. The fire at Takht-i Soleiman was called ādur Wishnāsp and was dedicated to the arteshtar or warrior class of the Sasanid.

Folk legend relates that King Solomon used to imprison monsters inside the 100 m deep crater of the nearby Zendan-e Soleyman “Prison of Solomon”. Another crater inside the fortification itself is filled with spring water; Solomon is said to have created a flowing pond that still exists today. Nevertheless, Solomon belongs to Semitic legends and therefore, the lore and namesake (Solomon’s Throne) should have been formed following Arab conquest of Persia. A 4th century [citation needed] Armenian manuscript relating to Jesus and Zarathustra, and various historians of the Islamic period, mention this pond. The foundations of the fire temple around the pond is attributed to that legend. Takht-E Soleyman appears on the 4th century Peutinger Map.

Archaeological excavations have revealed traces of a 5th-century BC occupation during the Achaemenid period, as well as later Parthian settlements in the citadel. Coins belonging to the reign of Sassanid kings, and that of the Byzantine emperor Theodosius II (AD 408-450), have also been discovered there.

Takht-e-Solyman-Iran

The Armenian Monastic Ensembles:

The Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran, located in the West Azerbaijan and East Azerbaijan provinces in Iran, is an ensemble of three Armenian churches that were established during the period between the 7th and 14th centuries A.D. The edifices—the St. Thaddeus Monastery, the Saint Stepanos Monastery, and the Chapel of Dzordzor—have undergone many renovations. These sites were inscribed as cultural heritages in the 32nd session of the World Heritage Committee on 8 July 2008 under the UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The three churches lie in a total area of 129 hectares (320 acres) and were inscribed under UNESCO criteria (ii), (iii), and (vi) for their outstanding value in showcasing Armenian architectural and decorative traditions, for being a major centre for diffusion of Armenian culture in the region, and for being a place of pilgrimage of the apostle St. Thaddeus, a key figure in Armenian religious traditions. They represent the last vestiges of old Armenian culture in its southeastern periphery. The ensemble is in a good state of preservation.

Armenian Monastic Ensembles

The Bisotun Relief:

The Behistun Inscription (also Bisotun, Bistun or Bisutun , Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning “the place of god”) is a multilingual inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah Province of Iran, near the city of Kermanshah in western Iran. It was crucial to the decipherment of cuneiform script.

Authored by Darius the Great sometime between his coronation as king of the Persian Empire in the summer of 522 BC and his death in autumn of 486 BC, the inscription begins with a brief autobiography of Darius, including his ancestry and lineage. Later in the inscription, Darius provides a lengthy sequence of events following the deaths of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses II in which he fought nineteen battles in a period of one year (ending in December 521 BC) to put down multiple rebellions throughout the Persian Empire. The inscription states in detail that the rebellions, which had resulted from the deaths of Cyrus the Great and his son Cambyses II, were orchestrated by several impostors and their co-conspirators in various cities throughout the empire, each of whom falsely proclaimed kinghood during the upheaval following Cyrus’s death.

Darius the Great proclaimed himself victorious in all battles during the period of upheaval, attributing his success to the “grace of Ahura Mazda”.

The inscription includes three versions of the same text, written in three different cuneiform script languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a variety of Akkadian). The inscription is to cuneiform what the Rosetta stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs: the document most crucial in the decipherment of a previously lost script.

The inscription is approximately 15 metres high by 25 metres wide and 100 metres up a limestone cliff from an ancient road connecting the capitals of Babylonia and Media (Babylon and Ecbatana, respectively). The Old Persian text contains 414 lines in five columns; the Elamite text includes 593 lines in eight columns, and the Babylonian text is in 112 lines. The inscription was illustrated by a life-sized bas-relief of Darius I, the Great, holding a bow as a sign of kingship, with his left foot on the chest of a figure lying on his back before him. The supine figure is reputed to be the pretender Gaumata. Darius is attended to the left by two servants, and nine one-meter figures stand to the right, with hands tied and rope around their necks, representing conquered peoples. Faravahar floats above, giving his blessing to the king. One figure appears to have been added after the others were completed, as was Darius’s beard, which is a separate block of stone attached with iron pins and lead.

bisotun

Meymand Village:

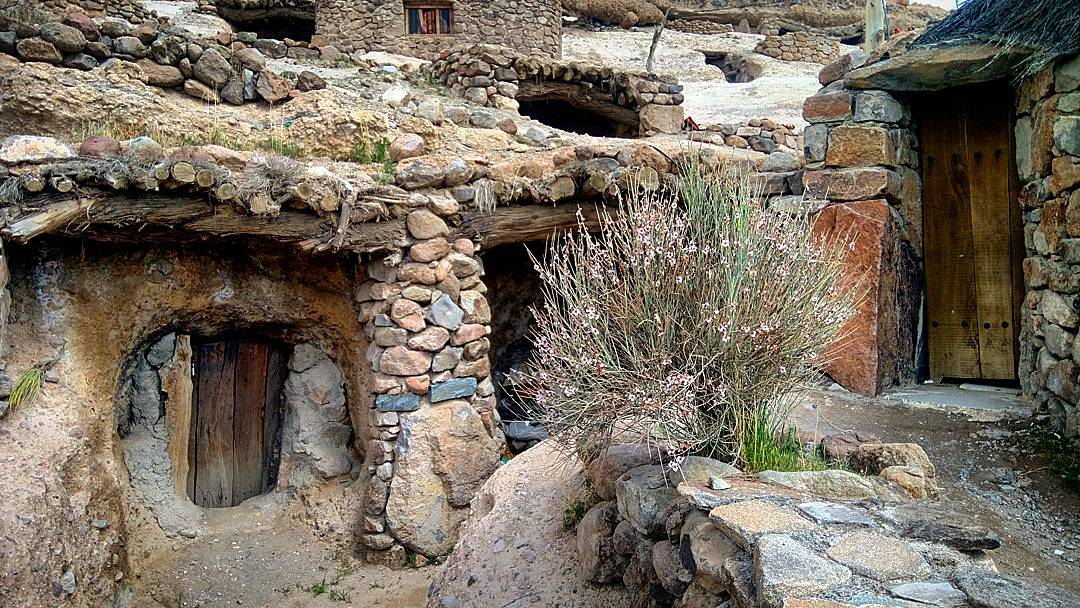

Meymand (Romanized as Maymand, Meimand and Maimand) is a village in Meymand Rural District, in the Central District of Shahr-e Babak County, Kerman Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 673, in 181 families.

Meymand is a very ancient village which is located near Shahr-e Babak city in Kerman Province, Iran. Meymand is believed to be a primary human residence in the Iranian Plateau, dating back to 12,000 years ago. Many of the residents live in the 350 hand-dug houses amid the rocks, some of which have been inhabited for as long as 3,000 years. Stone engravings nearly 10,000 years old are found around the village, and deposits of pottery nearly 6,000 years old attest to the long history of settlement at the village site.

Regarding the origin of these structures two theories have been suggested: According to the first theory, this village was built by a group of the Aryan tribe about 800 to 700 years B.C. and at the same time with the Median era. It is possible that the cliff structures of Meymand were built for religious purposes. Worshippers of Mithras believe that the sun is invincible and this guided them to consider mountains as sacred. Hence the stone cutters and architects of Meymand have set their beliefs out in the construction of their dwellings. Based on the second theory the village dates back to the second or third century A.D. During the Arsacid era different tribes of southern Kerman migrated in different directions. These tribes found suitable places for living and settled in those areas by building their shelters which developed in time into the existing homes. The existence of a place known as the fortress of Meymand, near the village, in which more than 150 ossuaries (bone-receptacle) of the Sassanid period were found, strengthens this theory.

Living conditions in Meymand are harsh due to the aridity of the land and to high temperatures in summers and very cold winters. [citation needed] The local language contains many words from the ancient Sassanid and Pahlavi languages.

In 2005, Meymand was awarded the UNESCO-Greece Melina Mercouri International Prize for the Safeguarding and Management of Cultural Landscapes (about $20,000).

On 4 July 2015, the village was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites list.

meymand

The Golestan Palace:

The Golestan Palace (Kākh-e Golestān) is the former royal Qajar complex in Iran’s capital city, Tehran.

One of the oldest historic monuments in the city of Tehran, and of world heritage status, the Golestan Palace belongs to a group of royal buildings that were once enclosed within the mud-thatched walls of Tehran’s arg (“citadel”). It consists of gardens, royal buildings, and collections of Iranian crafts and European presents from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Golestan-Palace-Tehran

Sheikh Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble:

Sheikh Safi al-Din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble is the tomb of Sheikh Safi-ad-din Ardabili located in Ardabil, Iran. In 2010, it was registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Sheikh Safi, an eminent leader of an Islamic Sufi order established by the Safavids, was born in Ardabil where this complex is located. The Safavids valued the tomb-mosque form, and the tomb with its mausoleum and prayer hall is located at a right angle to the mosque. The buildings in the complex surround a small inner courtyard (31 by 16 meters). The complex is entered through a long garden.

The Mausoleum of Sheikh Safi, in Ardabil, was first built by his son Sheikh Sadr al-Dīn Mūsā, after Sheikh Safi’s death in 1334. It was constructed between the beginning of the 16th century and the end of the 18th century. The mausoleum, a tall, domed circular tower decorated with blue tile and about 17 meters in height; beside it is the 17th-century Porcelain House preserving the sanctuary’s ceremonial wares. Also part of the complex are many sections that have served a variety of functions over the past centuries, including a library, a mosque, a school, mausolea, a cistern, a hospital, kitchens, a bakery, and some offices. It incorporates a route to reach the shrine of the sheikh divided into seven segments, which mirror the seven stages of Sufi mysticism. Various parts of the mausoleum are separated by eight gates, which represent the eight attitudes of Sufism.

Several parts were gradually added to the main structure during the Safavid dynasty. A number of Safavid sheikhs and harems and victims of the Safavids’ battles, including the Battle of Chaldiran, have been buried at the site.

safiodin-ardebili

The Lut Desert:

The Lut Desert, widely referred to as Dasht-e Lut (“Emptiness Plain”), is a large salt desert located in the provinces of Kerman and Sistan and Baluchistan, Iran. It is the world’s 27th-largest desert, and was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List on July 17, 2016. The surface of its sand has been measured at temperatures as high as 70 °C (159 °F), making it one of the world’s driest and hottest places.

lut-desert

Soltaniyeh Dome:

Soltaniyeh (Romanized as Solţānīyeh, Solţāneyyeh, Sultaniye, and Sultānīyeh; also known as Sa‘īdīyeh; Latin: Soltania/ Sultania) is the capital city of Soltaniyeh District of Abhar County, Zanjan Province, Azerbaijan, northwestern Iran.

Soltaniyeh, located some 240 kilometres (150 mi) to the north-west of Tehran, was built as the capital of Mongol Ilkhanid rulers of Iran in the 14th century. Its name which refers to the Islamic ruler title sultan translates loosely as “the Regal”.

In 2005, UNESCO listed Soltaniyeh as one of the World Heritage Sites. The road from Zanjan to Soltaniyeh extends until it reaches to the Katale khor cave.

William Dalrymple notes that Öljaitü intended Soltaniyeh to be “the largest and most magnificent city in the world” but that it “died with him” and is now “a deserted, crumbling spread of ruins.

Soltaniyeh-dome-zanjan

Persian Gardens:

The tradition and style of garden design represented by Persian gardens or Iranian gardens has influenced the design of gardens from Andalusia to India and beyond. The gardens of the Alhambra show the influence of Persian garden philosophy and style in a Moorish palace scale, from the era of al-Andalus in Spain. Humayun’s Tomb and Taj Mahal have some of the largest Persian gardens in the world, from the era of the Mughal Empire in India.

Persian gardens may originate as early as 4000 BCE. [dubious – discuss] [verification needed] Decorated pottery of that time displays the typical cross plan of the Persian garden. The outline of Pasargadae, built around 500 BCE, is viewable today.

During the reign of the Sasanian Empire (third to seventh century), and under the influence of Zoroastrianism, water in art grew increasingly important. This trend manifested itself in garden design, with greater emphasis on fountains and ponds in gardens.

During the Islamic period, the aesthetic aspect of the garden increased in importance, overtaking utility. During this time, aesthetic rules that govern the garden grew in importance. An example of this is the chahār bāgh, a form of garden that attempts to emulate the Garden of Eden, with four rivers and four quadrants that represent the world. The design sometimes extends one axis longer than the cross-axis, and may feature water channels that run through each of the four gardens and connect to a central pool.

The invasion of Persia by the Mongols in the thirteenth century led to a new emphasis on highly ornate structure in the garden. Examples of this include tree peonies and chrysanthemums. [clarification needed] The Mongols then carried a Persian garden tradition to other parts of their empire (notably India).

Babur introduced the Persian garden to India. The now unkempt Aram Bagh, Agra was the first of many Persian gardens he created. The Taj Mahal embodies the Persian concept of an ideal paradise garden.

The Safavid dynasty (seventeenth to eighteenth century) built and developed grand and epic layouts that went beyond a simple extension to a palace and became an integral aesthetic and functional part of it. In the following centuries, European garden design began to influence Persia, particularly the designs of France, and secondarily that of Russia and the United Kingdom. Western influences led to changes in the use of water and the species used in bedding.

Traditional forms and style are still applied in modern Iranian gardens. They also appear in historic sites, museums and affixed to the houses of the rich.

Elements of the Persian garden, such as the shade, the jub, and the courtyard style hayāt in a public garden in Shiraz.

Sunlight and its effects were an important factor of structural design in Persian gardens. Textures and shapes were specifically chosen by architects to harness the light.

Iran’s dry heat makes shade important in gardens, which would be nearly unusable without it. Trees and trellises largely feature as biotic shade; pavilions and walls are also structurally prominent in blocking the sun.

The heat also makes water important, both in the design and maintenance of the garden. Irrigation may be required, and may be provided via a form of underground tunnel called a qanat, that transports water from a local aquifer. Well-like structures then connect to the qanat, enabling the drawing of water. Alternatively, an animal-driven Persian well would draw water to the surface. Such wheel systems also moved water around surface water systems, such as those in the chahar bāgh style. Trees were often planted in a ditch called a juy, which prevented water evaporation and allowed the water quick access to the tree roots.

The Persian style often attempts to integrate indoors with outdoors through the connection of a surrounding garden with an inner courtyard. Designers often place architectural elements such as vaulted arches between the outer and interior areas to open up the divide between them.

Eram-Garden-Shiraz-HD