Nain Attraction Spots

Nain lies 170 km north of Yazd, and 140 km east of Isfahan. With an area of almost 35,000 km², Nain lies at an altitude of 1545 m above sea level. Like much of the Iranian plateau, it has a desert climate, with a maximum temperature of 41 °C in summer, and a minimum of -9 °C in winter.

More than 3,000 years ago, Persians learned how to construct aqueducts underground to bring water from the mountains to the plains. In the 1960s, this ancient system provided more than 70 percent of the water used in Iran. Nain is one of the best places in the whole world to see these qanats functioning.

Unique to Nain are some of the most outstanding monuments of Iran: the Jame Mosque, one of the first four mosques built in Iran after the Arab invasion; the Pre-Islamic Narej Fortress; a Pirnia traditional house; the Old Bazaar; Rigareh, a qanat-based watermill; and a Zurkhaneh (a place for traditional sport).

Besides its magnificent monuments, Nain is also famous for high-quality carpets and wool textile and home- made pastry called “copachoo.” Some linguists believe the word “Nain” may have been derived from the name of one of the descendants of the prophet Noah, who was called “Naen”. Many local people speak an ancient Sasani Pahlavi dialect, the same dialect spoken by the Zoroastrians in Yazd today. Other linguists state that the word Nain is derived from the word “Nei” (“straw” in English) which is a marsh plant.

Nain Congregational Mosque

Nain’s congregational mosque is one of the oldest mosques in Iran. But it still has its original architecture and is in use and protected by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization. According to the French professor, Arthur Pops, the mosque’s foundation dates back to the 9th century. It has a very simple plan, but very beautiful. The mosque contains a central rectangular courtyard that is surrounded by hypostyles on three sides. At one of these hypostyles, the mihrab of the mosque is located. It is a niche on the wall that shows the direction of “Qebleh” in Mecca, the holy city that Moslems pray toward five times a day. This mihrab has an amazing stucco work decoration, probably created during the 9th or the 10th century. Beside it, there is a wooden altar with delicate wooden inlay work. The Mosque also has a 28-meter-high minaret belonging to the Seljuk Era, the 10th century.

Pirnia Traditional House

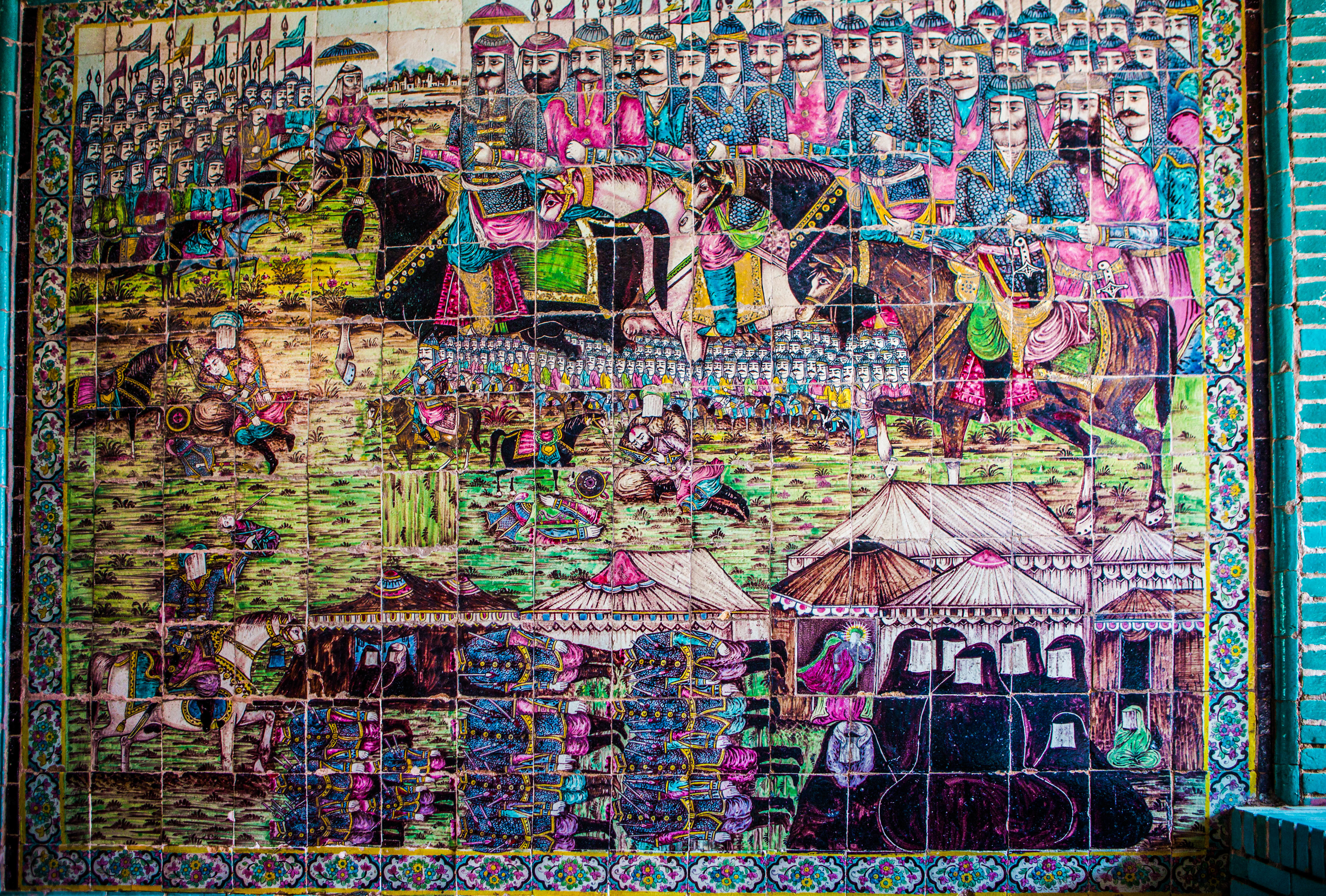

Pirnia traditional house and ethnology museum is situated opposite the congregational mosque. A typical example of this region’s desert houses, in terms of architecture and art, belonging to the Safavid Period. The house consists of an exterior, an interior, a deep garden, a silo room and all the facilities of a lord’s house. When you enter the house and pass the first corridor, you reach an octagonal room called “hashti”, a waiting room for visitors. Beautiful paintings, amazing plasterwork of Qur’an stories, a book of famous poems and calligraphy frames decorate the living room. First, the judge of Nain lived there. Then, during the Qajar Period, the governor of Nain lived in this house. Just a few decades ago, the house was purchased by the Ministry of Culture and Art. After renovation in 1994, the house was converted into the desert ethnology museum.

Nain’s Mosallah edifice

Nain’s Mosallah edifice is another must-see. Its vast garden was a popular recreational area until recently. The mausoleum inside the Mosallah was a pilgrimage site for visitors. There is a water reservoir (ab-anbar) on one side of the garden, which can be accessed through a stairway. Water in this reservoir got cooled by two wind towers. It was in use until a few years ago. The architectural style of Mosallah has the characteristics of Qajar dynasty, and a number of literary, political and religious figures are buried at this site. “Mosallah” is an Arabic word for a place of prayer, but no one knows if any praying was ever done at this location. Mosallah is an octagonal mausoleum of dervishes and Qajar and Pahlavi political figures. It’s encompassed by a military fort from Qajar era, with a high wall. The pistachio trees around the turquoise-domed mausoleum and two tall wind towers make the complex really photogenic.

Narin Ghale

Narin Ghal’e is one of the most important monuments of the province dating back to the period before the advent of Islam in Iran, and has been recorded as one of the national buildings. This ancient castle has been constructed on top of Galeen hill and overlooks the city. It seems that upper floors of the building have been reconstructed and belong to the Islamic era. One part of the building was destroyed in the course of road construction during the reign of Pahlavi II.

is one of the most important monuments of the province dating back to the period before the advent of Islam in Iran, and has been recorded as one of the national buildings. This ancient castle has been constructed on top of Galeen hill and overlooks the city. It seems that upper floors of the building have been reconstructed and belong to the Islamic era. One part of the building was destroyed in the course of road construction during the reign of Pahlavi II.

Nain’s bazaar

Nain’s bazaar is a remarkable historical attraction. It extends 340 m from the Gate of Chehel Dokhtaran to Khajeh Khezr mosque, and is connected by main alleys, and tributary passages, to various neighbourhood centers. The bazaar has two main crossroads (chahar su). Parts of it have been renovated, and its many varied stalls were active until a few years ago. However, at present, the bazaar is almost deserted, since the retailers have moved to the city’s street shops. Some important monuments, such as the Sheikh Maghrebi mosque, Khajeh mosque, and Chehel Dokhtaran’s Hosseinieh are nearby.

Fatemi House

Fatemi House is the largest traditional house in Nain. It’s opposite Narin Castle, beside the old bazaar. The house belonged to a very influential family in Nain. It consists of a large number of sections, each with a different function: summer and winter living rooms, resting rooms, stable, silos, corridors, dining rooms for guests, and other facilities. Most of the rooms are furnished with stained glass windows, inlaid wooden doors, and plasterwork. The house belongs to the Cultural Heritage Organization.